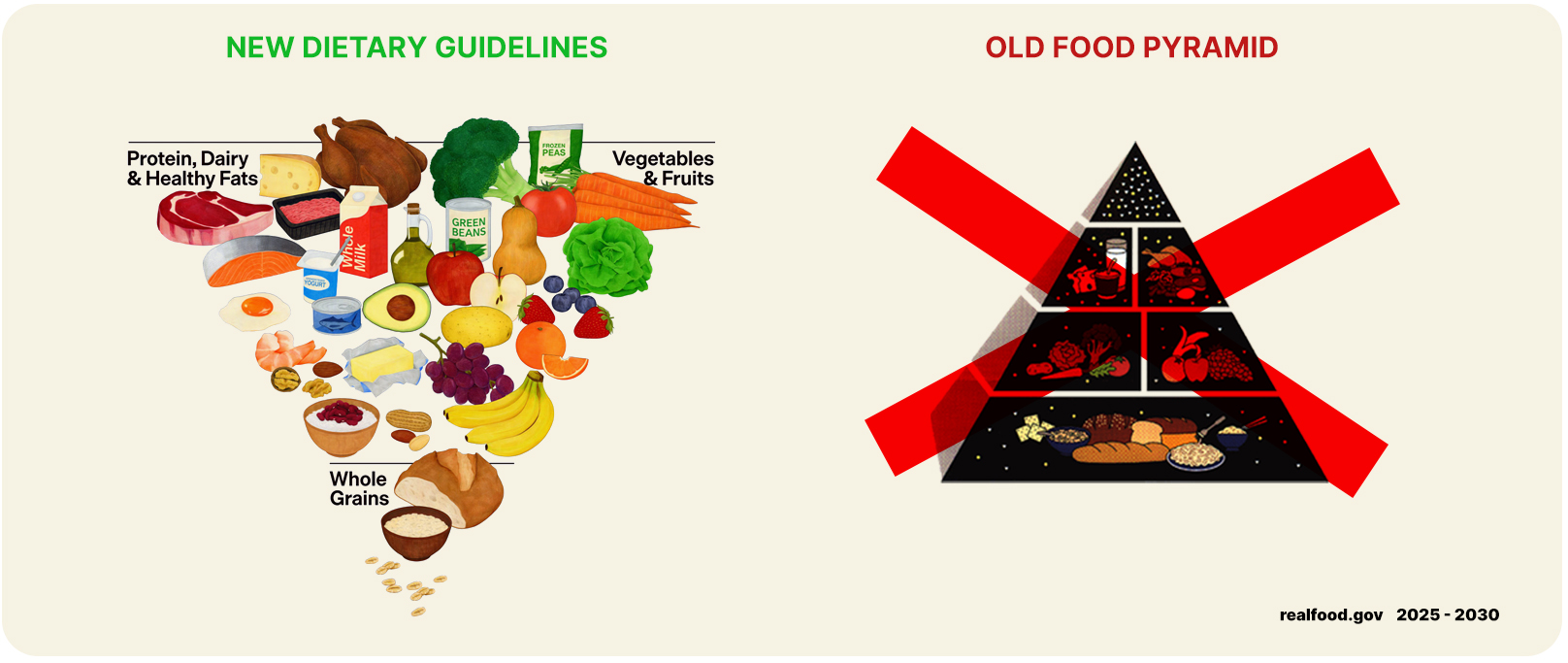

The 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) mark a meaningful shift in how nutrition guidance is framed. While still designed for population-level advice, the underlying Scientific Foundation for the DGA, 2025–2030 reflects a more nuanced understanding of individual variability, metabolic health, and insulin resistance.

For individuals with metabolic conditions, and for the practitioners guiding them, these changes matter. Compared with previous editions, the new DGA allow greater flexibility, but also place greater responsibility on personalized, outcome-driven nutrition decisions.

In this article, we interpret the key changes in the DGA through a metabolic health lens and outline what they mean for real-world decision-making.

Key points from the new DGA

1. Carbohydrate reduction is recognized as a valid approach in metabolic disease

For the first time, the DGA explicitly recognize low-carbohydrate dietary patterns as a scientifically justified option for individuals with chronic metabolic disease, including obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Insulin resistance is identified as a central driver of metabolic disease, linking excessive carbohydrate intake to chronically elevated insulin levels, impaired glycemic control and cardiometabolic risk. In this context, low-carbohydrate diets are evaluated as a logical and coherent strategy to reduce glycemic load, lower insulin demand, and improve metabolic outcomes.

This represents a notable shift: carbohydrate reduction is no longer positioned as a non-standard approach, but as a clinically relevant option.

What this means for individuals

- If you have insulin resistance and poor glycemic control, or you would like to prevent it, carbohydrate intake matters.

- Lowering carbohydrates can reduce glucose excursions, insulin demand, and overall metabolic strain, supporting your metabolic health.

- You should feel empowered to ask your healthcare provider about low-carbohydrate approaches and how they may be beneficial for your metabolic health.

What this means for practitioners

- Carbohydrate reduction is now explicitly supported as part of evidence-based metabolic therapy for individuals with chronic metabolic disease.

- This creates space for collaborative discussions with patients about carbohydrate reduction as the core of their metabolic care

2. Individuality, outcomes, and the end of one-size-fits-all nutrition

A recurring theme in the Scientific Foundation is interindividual variability. The evidence reviewed consistently shows that people respond differently to the same dietary pattern depending on insulin sensitivity, baseline metabolic health, physical activity, age, sex, and disease state. As a result, uniform dietary prescriptions can produce widely divergent metabolic outcomes.

Building on this, the focus shifts away from rigid dietary rules toward measuring real metabolic effects, such as how blood biomarkers, weight, and other health markers respond to food choices. This acknowledges that broad recommendations may not reflect how a given individual will respond.

What this means for individuals

- There is no single “correct” calorie or macronutrient intake that works for everyone.

- Your metabolic response matters more than adherence to a generic recommendation.

- Tracking relevant biomarkers can help you understand your own response to food and adjust your approach accordingly.

What this means for practitioners

- Nutrition guidance can and should be individualized based on metabolic status and clinical goals.

- Tracking biomarkers and having data-driven conversations with your patients support personalized, outcome-based decision-making.

3. Protein is emphasized. Fat guidance remains contradictory

New emphasis is placed on nutrient-dense, minimally processed foods as the foundation of a healthy dietary pattern, including foods that naturally provide protein, fats, and essential micronutrients.

Within this framework, protein adequacy receives unprecedented attention. The new DGA support protein intake ranges of approximately 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day, nearly double the long-standing reference intake of 0.8 g/kg/day. This represents a meaningful shift away from minimum protein requirement and toward recognizing protein’s role in metabolic health, physical function, satiety, and preservation of lean mass, particularly in midlife, older age, and in individuals with metabolic risk.

The DGA also emphasize protein quality, noting the importance of nutrient-dense protein sources that contribute essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Many of these foods (such as meat, eggs, dairy, and fish) naturally contain both protein and fat, including saturated fat.

At the same time, the long-standing recommendation to limit saturated fat to <10% of total energy intake remains unchanged. This persists despite the Scientific Foundation acknowledging that causal evidence from randomized controlled trials does not demonstrate that reducing saturated fatty acids to <10% of energy lowers cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

This results in an internal tension: whole, protein-rich foods are encouraged, yet some of their naturally occurring fats remain constrained by population-level caps.

What this means for individuals

- Whole, protein-rich, minimally processed foods are prioritized over low-fat, ultra-processed alternatives.

- Protein intake plays a central role in metabolic health, satiety, and maintenance of lean mass.

- For those following low-carbohydrate approaches, adhering to the saturated fat cap may be challenging and not clearly aligned with outcome-based evidence.

What this means for practitioners

- Protein targets will need to be reconsidered in light of updated guidance, especially for patients with metabolic disease, aging-related muscle loss, or increased protein needs.

- Application of the saturated fat cap requires clinical context, rather than automatic enforcement.

- Metabolic health, lipid responses, and insulin sensitivity should guide recommendations on overall dietary patterns.

4. Rapidly digestible carbohydrates strain metabolic health

A strong message in the Scientific Foundation is that rapidly digestible carbohydrates drive adverse metabolic effects, whether they come from added sugars or refined starches.

Refined starches such as white flour, refined grains, and many processed foods are absorbed quickly and place substantial demands on insulin-mediated glucose regulation. While their composition differs, both refined starches and added sugars deliver rapidly available carbohydrates that can impair metabolic health when consumed frequently.

Added sugars are therefore not a separate metabolic concern, but part of a broader category of carbohydrates that are not required for health and are best consumed in lower amounts.

How this translates into practical guidance:

- Carbohydrate choice: when carbohydrates are included, prioritizing minimally processed, whole-grain sources over refined grains helps slow absorption and reduce insulin demand.

- Rapidly digestible carbohydrates: minimizing exposure supports metabolic health

- Infants and children up to 10 years: the recommendation is no added sugars, reflecting increased vulnerability during early metabolic development.

- Adults: if consumed at all, keeping added sugar to no more than 10 g per meal helps limit cumulative metabolic stress across the day.

What this means for individuals

- Refined starches and added sugar are not a required part of a healthy diet, and reducing exposure supports metabolic health.

- If rapidly digestible carbohydrates are consumed, keeping amounts small and infrequent, rather than concentrated or repeated throughout the day, may help limit metabolic strain.

- If carbohydrates are consumed, they should be from minimally processed sources (e.g., vegetables, whole grains)

What this means for practitioners

- Carbohydrate sources should be evaluated based on their glycemic and insulin effects.

- Shifting the conversation from “allowed amounts” to metabolic impact and frequency of exposure supports more effective, individualized care.

Takeaway: what this means for metabolic health

The 2025–2030 DGA emphasize real whole foods, adequate protein, healthy fats, and minimal refined carbohydrates, with dietary patterns assessed by their metabolic effects rather than rigid dietary rules.

For individuals, this means greater permission (and responsibility) to focus on how their body responds to whole foods, rather than following one-size-fits-all prescriptions.

For practitioners, it supports a shift toward personalized, outcome-driven nutrition care. It also means greater flexibility to prescribe carbohydrate reduction and use biomarkers to guide care.

In this framework, measuring what matters and adjusting accordingly becomes central to improving metabolic health, both in prevention and in the management of chronic disease.

References

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025-2030

Scientific Foundation for the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030